Appalachian Farmers and the Spirit of the Mountains in Southwest Virginia

Author:

The early morning mist rolled down the slopes of the Appalachians, settling into the hollows like an old friend. The sun, still stretched behind the blue ridges, cast a muted orange glow over fields of corn, tobacco, and hay. This was the heartbeat of Southwest Virginia, a land both beautiful and unforgiving, where farmers carried the weight of their traditions on backs as strong as the mountains themselves.

Life here had always demanded grit. “If ya don’t plant it, you don’t eat it,” was more than just a saying; it was a creed passed from one calloused hand to the next. The soil, rocky and hard to work, seemed to test a farmer’s resolve at every turn. Yet, every spring, the same fields breathed with possibility, plowed and planted by men and women who understood the delicate, almost sacred relationship between labor and survival.

For those tending these fields in the late 1960s and 1970s, life was a constant balancing act between the old ways and the economic shifts pressing on rural America. The advent of modern machinery occasionally felt like a double-edged sword. One news clipping from 1972 described how a struggling farmer, John Maddox, rigged an aging tractor with spare parts scavenged from a scrapyard. “Good enough’ll have to do,” he joked, though his weary face betrayed countless hours of trial and error. Such stories abounded, not as tales of woe but as proof that resilience was stitched into the fabric of this community.

Even the landscape seemed to reflect the duality of hardship and hope. The rolling hills of the Appalachians, with their thick forests and winding creeks, offered a quiet beauty, yet their steep incline turned even the simplest tasks into Herculean efforts. Farmers would haul water from the creeks in old metal buckets, their boots sinking into the mud as they wrestled gravity itself. “A hill always seems steeper when you’re carrying two buckets,” old-timers would say with an air of wry humor, though there was no complaint in their tone—just truth.

Mornings began early, with roosters crowing and the steady thrum of a wood-burning stove warming the kitchen. The smell of biscuits and sawmill gravy filled the air as families gathered around battered kitchen tables. Mealtime was sacred. It wasn’t just food; it was fuel for the day ahead, and a moment to share stories or enjoy a rare laugh before the weight of work bore down. Even the simplest of meals seemed touched by the land—a gift from the fields and gardens tilled tirelessly through sweltering summers.

Traditions thrived here, passed down not just in words but through actions. Quilting bees brought women together to craft intricate patterns, each stitch a memory to be preserved. Barn raisings saw neighbors coming together, every hand lifting beams into place in a symphony of shared labor and purpose. Nothing was wasted because nothing could be. Scraps of a Sunday ham would stretch into a week’s worth of meals, the bone boiled for soup until there was nothing left to give.

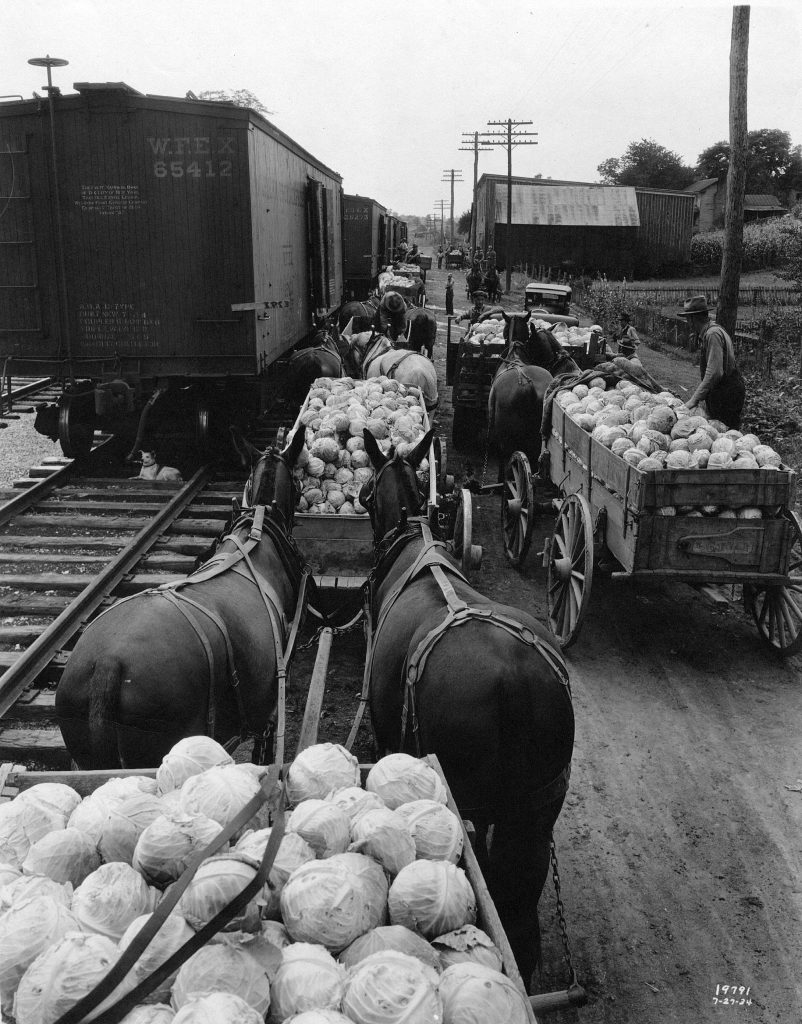

At harvest time, the community came alive. Men piled bales of hay onto wagons creaking under the strain, while women canned fruits and vegetables late into the night, sealing jars with the unmistakable “pop” that meant their efforts were safe for the winter. Tobacco leaves, hung to dry in weathered barns, lent the air a mix of sweetness and tang. The long days of harvest ended in backbreaking exhaustion, but closing the barn doors at dusk came with a deep sense of accomplishment.

There were lean years, to be sure. Droughts in the summer, floods in the spring—each season seemed to carry its own set of trials. Yet the people persevered because that’s what you did. “The good Lord’s will and a little elbow grease’ll get you farther than bellyachin’,” an elderly farmer once said to a young neighbor at the general store, wisdom drawn from decades of simply refusing to give up.

Churches, with their white clapboard steeples rising against the gray-green mountainside, served as both spiritual centers and social hubs. Come Sunday, the pews were filled with men in overalls and women in worn dresses, voices lifting in harmony to classic hymns like “Amazing Grace.” Afterward, the parking lot buzzed with conversation—news of a neighbor’s new calf, advice for patching a leaky barn roof, and maybe even a slice of molasses cake shared from the back of a pickup.

This was life in the Appalachian Mountains, where beauty and struggle walked hand in hand, and where farming families defined themselves not by what they lacked, but by what they endured. Resilience and resourcefulness weren’t just admirable traits here; they were lifelines, tethering generations to their roots even as the world beyond changed faster than the mountain mist could rise.

Looking back on this era, it’s clear that these farmers carried something greater than the weight of their tools or crops. They bore the invisible mantle of preserving a way of life that valued hard work, community, and an unshaken hope in tomorrow. The mountains tested them, but never broke them. Like the hickory trees that dotted their ridges, their roots ran deep, their branches reaching toward whatever light they could find. And through it all, they stood tall, as they always had, refusing to bow to the winds of circumstance. — Luther Taylor